The Gould Coupler Strike of 1914

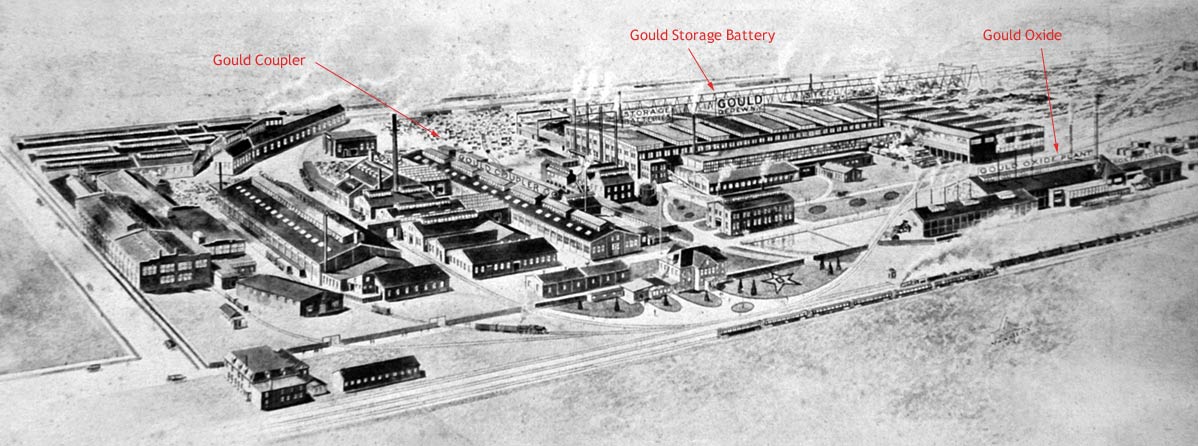

Gould campus c. 1910. Image Courtesy of Lancaster Historical Society

The Gould Coupler plant and other Gould Company industries at the same location off Transit Road in Depew came into existence because of Chauncey Depew. President of the New York Central Railroad in 1885, he determined to build facilities outside Buffalo to maintain his trains. As part of his plan, he interested a number of Buffalo investors including John J. Albright, George Urban, Wilson Bissell, and Charles Gould in creating the Depew Improvement Company and in buying land for what may have been the region's first industrial park. The company purchased 1,000 acres in what became named informally, then formally in 1894, Depew. Four railroads crossed the land purchased by this company: New York Central, Lehigh Valley Railroad, Erie Railroad, and D. L. & W. By 1900, numerous heavy industries had been constructed in a very short time. These included the New York Central shops employing 1,000; nearly 1,000 more worked for Gould Coupler, Gould Storage Battery, the American Car and Foundry, Magnus Metal, Steel Tire Whee, the Pullman Company, Union Car, Buffalo Brass Company, and Wagner Palace Car Works.

Model of the Janney railroad coupler manufactured at the Gould Coupler plant in Depew. Image source: photo of display at the Lancastter Historical Society.

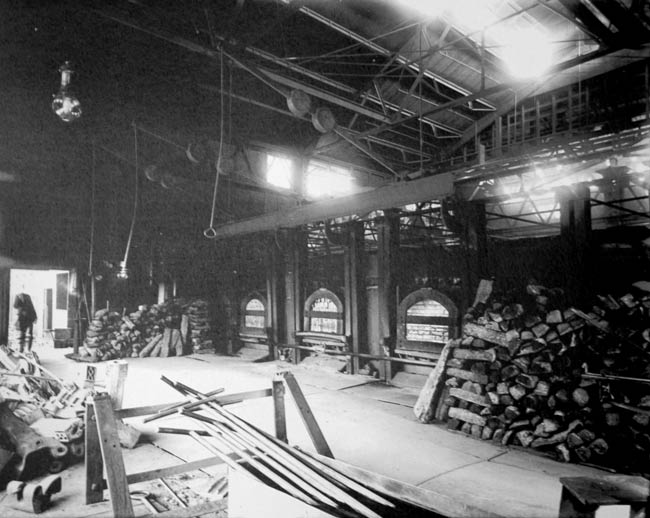

Interior of the Gould Plant, c. 1900. Image courtesy of the Lancaster Historical Society.

On January 2, 1914, the Buffalo Evening News reported that in the previous year, 101,149 trade union members in New York State were idle because of a lack of work. That was the highest number in seventeen years with the exception of 1908. And on January 1, 1914, the Gould Coupler plant received a new manager, G. W. Hayden who announced changes to working conditions and schedules of the unionized workforce. He made no secret of his intention to break the union at Gould Coupler. The stage was set for a long and violent strike.

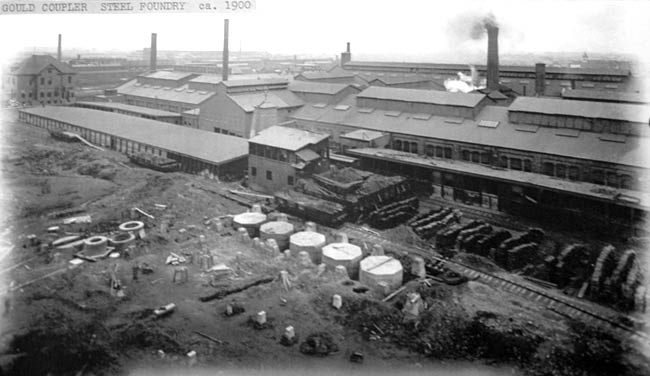

Exterior view of the Gould plant, c. 1900. Image courtesy of the Lancaster Historical Society.

Hayden decided to improve profitability in the plant by lengthening the work day from 9 hours to 9.5 hours. He also ordered the men not to smoke and he eliminated the sandwich break at 9 a.m. This last order would require men who commuted from the city, eating before 6 a.m., to wait until noon for their first food break. Company owner Charles Gould claimed he paid the highest wages in the United States, but he paid his workers on a piece work basis at around $3.50 per day, at least a dollar less than plants in other regions. For 8 years, the only union demand had been for an increase of $.25 per day for day work. The company had ignored those requests and responded that it wanted a reduction in the rate of piece work, to which the union had agreed. Throughout the strike, Gould would receive little public support.

The International Molders Union of North America Locals 442 and 260 sent a committee to meet with the new management regarding the new rules. They were fired and replaced with nonunion workers.

Exterior view of the Gould plant, c. 1900. Image courtesy of the Lancaster Historical Society.

By February, the 900 union members were on strike. The company responded by stocking up on large quantities of bedding, groceries, and other supplies for a strikebreaking workforce. The company also created a uniformed police force which temporarily roamed the village of Depew with billy clubs and shotguns; the village trustees directed the company to keep its force within the company grounds. Erie County sent fifteen deputies to help keep order.

Exterior view of the Gould plant, c. 1900. Image courtesy of the Lancaster Historical Society.

Strikebreakers hired were at first housed on the Gould grounds but objected to the conditions and, after a week, they were allowed to commute by train from Buffalo.

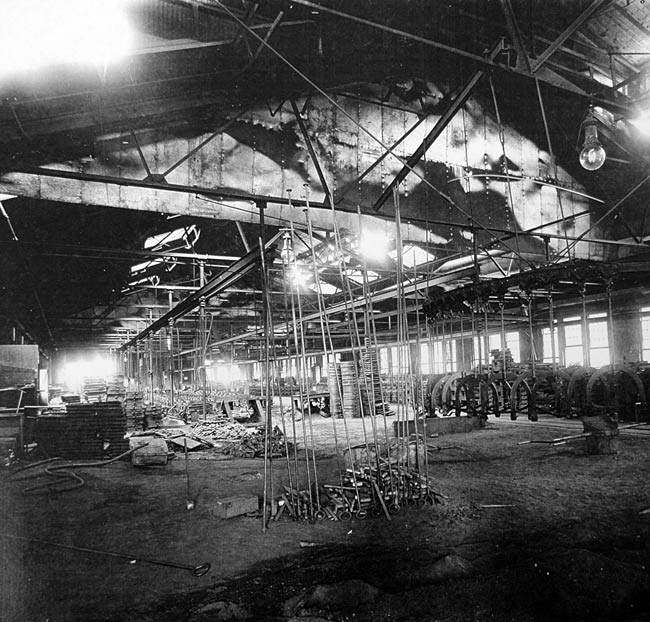

Interior view of the Gould plant, c. 1900. Image courtesy of the Lancaster Historical Society.

Company manager Hayden declared that he would not hire men from Lancaster and Depew to replace the striking workers. And so each day the work train from Buffalo brought 800 strikebreakers to the plant on the Lackawanna railroad. On March 23, over 200 men ambushed the work train outside Depew by blocking the tracks with timbers and then firing on the eleven rail cars carrying the strikebreakers. For around 10 minutes, a furious gunfight raged between the mob, armed with revolvers and rifles (rumored to have been sent from Buffalo) and the special police on the train. Surprisingly, only seven were found to have been shot, and one striker died. There were unconfirmed reports that a number of strikers were wounded but had been spirited away by their comrades to be cared for privately. The next day Gould evicted all residents of the company housing, located on the streets immediately east of the campus.

Image source: 1914 Buffalo Express (private collection).

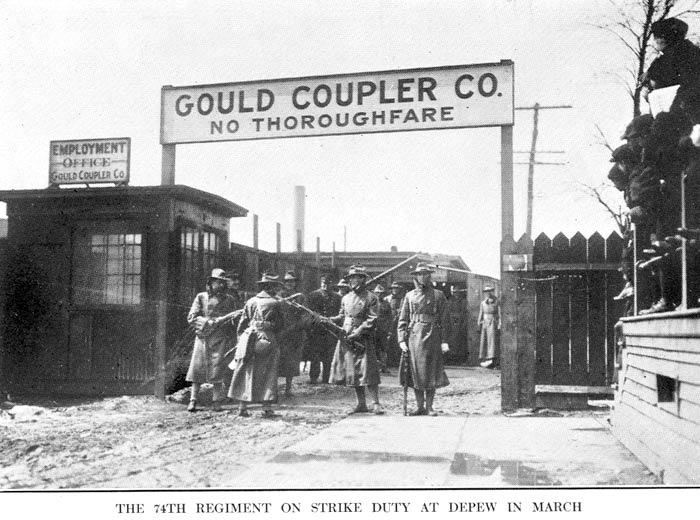

The Erie County Sheriff immediately called for help and the 74th Regiment (NY National Guard) was sent to establish order in Depew. Special trolley cars were sent to the Armory but the operators refused to transport the 900 soldiers as an act of solidarity with their union brothers, so the soldiers removed them from the cars and drove themselves to Depew. They established patrols in the village and placed armed squads on every street corner. Shots still were heard in the village during the night, but order returned to the little village of around 2,000 residents. Saloonkeepers were threatened with closure if they permitted agitations to originate in their establishments. The soldiers did not permit any gatherings on the streets. The Lancaster and Depew Village Boards asked that the overwhelming presence of uniformed troops be removed, but Erie County refused, fearing repercussions from the company and the railroad if further damages occured. The Buffalo Evening News stated that it was known that "a great many foreigners were armed."

Image source: 1914 Buffalo Express (private collection)

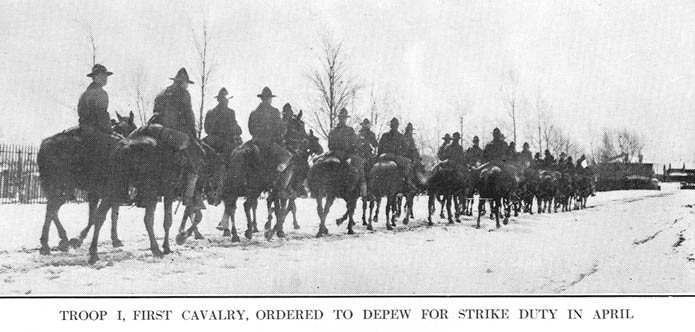

Within two weeks, the 74th was relieved by sixty mounted soldiers of the New York National Guard, Troop I, First Cavalry, commanded by Captain William J. Donovan. Their task was to patrol the village which they did in mounted pairs, carbines across their saddles, breaking up gatherings, closing saloons at 11 p.m. They remained two weeks, by which time the Erie County Sheriff had sworn 100 new deputies to take over the duties.

The strike continued. A few strikers were rehired on an individual basis by managers, but many had become discouraged, particularly regarding the troop presence, and left the area to seek work in other cities. Depew and Lancaster businessmen also complained that the strike and troops had reduced their business so that they feared it would take years to recover.

Troop I was relieved by April 13th. A grand jury, convened to investigate the March 23 riot, returned with eleven secret indictments of strikers, all of which eventually were dismissed. General Manager Hayden resigned August 31 and left town. Gould appointed J.O.Gould to replace Hayden and began to rebuild and expand his plants. Gould Coupler was now a non-union shop.

The former Gould campus. Google Maps

The Gould campus changed hands many times over the next century. In 1925, the foundry was purchased by the Symington Company, becoming Symington-Gould. During World War II, the plant converted to the manufacture of bomb casings and military tank components. Symington-Gould purchased the Wayne Pump Co. in 1958, a manufacturer of gasoling pumps and service station pumps. It became Symington-Wayne Corp. Ten years later, Dresser Industries purchased Symington-Wayne and formed the Dresser Transportation Division. The Depew plant closed in 1985. Today, parts of the campus are used by various businesses.

An excellent reference for this page was an article in 1997 The Lancaster Legend, by Terry Wolfe, entitled, "The Gould Coupler Strike of 1914." And special thanks is due to Town of Lancaster Historian Harley Scott for permitting use of photos from the Society's collection.